Tobacco harm reduction in the Middle East: an opportunity to lead by example

For decades, the world has grappled with the battle against the adverse health effects associated with tobacco consumption, and the Middle East – where the prevalence of cigarette smoking has traditionally been 20% of the adult population[1] on average – is certainly no different.

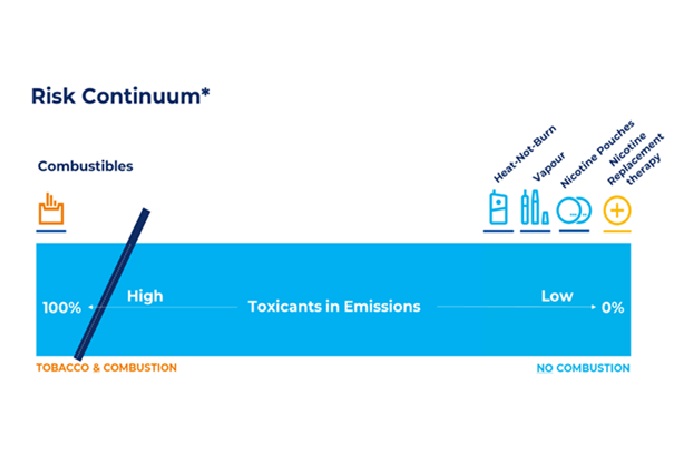

Tobacco harm reduction (THR), at its core, is a public health strategy that advocates for providing adult smokers, who choose not to quit, with reduced-risk* sources of nicotine. In this effort, THR may prove to be a valuable tool indeed.

This includes the ability to generate awareness among adult smokers, who would otherwise continue to smoke, about the advantages of making the switch to non-combustible alternatives. A growing body of credible research clearly demonstrates that the use of these products can help vast numbers of adult smokers not only give up cigarettes[2], but also greatly improve their quality of life[3] while reducing the risk of tobacco-related disease[4].

For example, one study found that in heat-not-burn (HNB) products, the concentration of tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) was one-fifth and carbon monoxide (CO) was one-hundredth of those contained by conventional cigarettes[5]. A systematic literature review also revealed that HNB products “reduced levels of harmful and potentially harmful toxicants by at least 62% and particulate matter by at least 75%”[6] compared to combustible products.

Meanwhile, the UK’s Royal College of Physicians has long maintained that “the hazard to health arising from long-term vapor inhalation is unlikely to exceed five percent of the harm from smoking tobacco”[7].

Global public perception, however, does not seem to be synonymous with expert opinion and research findings. In a telling, large-scale, international survey of 27,000 smokers from 28 countries, Ipsos, a multinational leader in market research and consulting, found that 74% of smokers across the world believe that vaping is at least as harmful as smoking cigarettes[8]. In fact, misinformation is so rampant in countries such as Brazil, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Kazakhstan that 80%[9] of smokers polled consider vaping to be more harmful than tobacco. These statistics illustrate the scale of the challenge facing public health officials, as well as the educational efforts and messaging needed to change perspectives.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East, consumer sentiment, in particular across the GCC countries, indicates varying levels of amenability to a transition to non-combustibles amongst adult smokers.

Local research conducted by Kantar, a global data, insights, and consulting company, shows that in the UAE, where 9.5% of consumers are currently using non-combustible products, a remarkable 83% are open to making the switch. This number certainly goes against the grain of the global sentiment recorded by the Ipsos survey. However, Saudi Arabia, where 14% of consumers presently use reduced-risk* alternatives, is significantly closer to worldwide figures, with 30% willing to give up conventional tobacco in 2023.

On a global scale, surveys and studies conducted indicate that adult smokers in various countries are generally interested in learning more about alternatives[10]. However, while significant percentages of consumers perceive them as less harmful than conventional tobacco (47% in Germany and 54% in France rank vaping the least harmful nicotine product[11]), as many as 9%[12] of smokers in both European nations consider vaping as the most harmful nicotine product. An astounding 11%[13] of them perceive cigarettes as the least detrimental option.

THR success stories, meanwhile, are becoming more frequent in those countries that have embraced the introduction and mass availability of reduced-risk* alternatives to conventional tobacco. In Japan, a country that was estimated to represent 85%[14] of global heat-not-burn (HNB) sales by 2018, cigarette sales declined from 197.5 billion units in 2011 to only 93.7 billion in 2021[15]. Subsequent studies have found that the steady decline in cigarette consumption is largely attributed to the introduction of HNBs in 2014, which have continued to grow and take market share from traditional cigarettes.[16]

By making reduced-risk* alternatives more accessible and affordable, governments can reduce healthcare costs associated with tobacco-related diseases.

At BAT, we also believe that a shift towards an evidence-based, risk-proportionate regulations of reduced-risk* alternatives could hold the key to accelerating the switch for adult smokers, who would otherwise continue to smoke, and reducing the smoking rates. Regulating non-combustible products in accordance with their position on the risk continuum represents a pragmatic and evidence-based approach to tobacco control that prioritizes harm reduction and public health outcomes. By recognizing the adoption of smokeless alternatives through risk-proportionate regulations, policymakers can empower adult smokers to make informed choices.

* Based on the weight of evidence and assuming a complete switch from cigarette smoking. These products are not risk free and are addictive.

[1] Kargar S, Ansari-Moghaddam A, (2023), “Prevalence of cigarette and waterpipe smoking and associated cancer incidence among adults in the Middle East”. Available at: https://www.emro.who.int/emhj-volume-29-2023/volume-29-issue-9/prevalence-of-cigarette-and-waterpipe-smoking-and-associated-cancer-incidence-among-adults-in-the-middle-east.html

[2] https://www.tobaccoharmreduction.net/benefits

[3] https://www.tobaccoharmreduction.net/lives-saved

[4] Levy DT, at al. (2017), “Potential deaths averted in USA by replacing cigarettes with e-cigarettes”. Available at: https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/tobaccocontrol/27/1/18.full.pdf

[5] Bekki K, et al. (2017), "Comparison of Chemicals in Mainstream Smoke in Heat-not-burn Tobacco and Combustion Cigarettes", Volume 39 Issue 3 Pages 201-207. Available at: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/juoeh/39/3/39_201/_article

[6] Simonavicius E, at al. (2018), “Heat-not-burn tobacco products: a systematic literature review”. Available at: https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/28/5/582

[7] Royal College of Physicians (2016), “Nicotine without smoke: Tobacco harm reduction”. Available at:

https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nicotine-without-smoke-tobacco-harm-reduction

[8] Fernández F, (2024), Opinion Poll “Innovation Under Fire: A Global Alert on the Misperception Epidemic in Vaping Views”. Available at: https://weareinnovation.global/opinion-poll-innovation-under-fire-a-global-alert-on-the-misperception-epidemic-in-vaping-views/

[9] Ibid.

[10] Chaplia M, et al. (2022), “Perceptions on Tobacco Harm Reduction and Nicotine in France and Germany with a global comparison”. Available at: https://consumerchoicecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Tobacco_HarmReduction_Nicotine_Perceptions_policy_paper_2022.pdf

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Watase Y, (2023), “Safer Nicotine Works: The Cases of Japan and Sweden”. Available at: https://tholosfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Tholos-Safer-Nicotine-Works.pdf

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.